SEATTLE — Gliding through the clear, emerald water of Puget Sound, Diver Laura James stopped when something shiny on the bottom caught her eye. She reached down and picked up a tire-flattened beer can.

And then she noticed more garbage — stir straws, bubble gum wrappers, coffee lids, a plastic packet of ketchup — littered across the sound’s sandy floor.

“I didn’t understand what I was seeing at first,” James says. “We’d swim along and we’d see this decaying swath – black with dead leaves and garbage. And then it would go back to normal.”

James, who has been diving in Puget Sound for more than 20 years, recalls the day she discovered the source. The giant submerged column she saw from a distance was in reality a dark plume of runoff flowing out of a pipe.

“It was just billowing and billowing,” James says. “It just made me feel almost helpless because it’s unstoppable.”

She asked herself, “How do we stop something that’s so much bigger than us?”

Stormwater is a toxic cocktail of sediment, grease, road grime, tire wear and any litter small enough to slip into storm drains.

And that’s just what can be seen. There’s much more.

Microscopic particles of heavy metals like zinc and copper are commonly found in urban runoff. There’s also oil and petroleum-based hydrocarbons. Fertilizers and pesticides also wash off lawns and into waterways. Even pet excrement contributes a significant amount of bacteria to urban creeks and streams.

Thursday marks the 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. When first took effect, stormwater pollution was not the top priority. What’s known as “point source pollution” — dumping of toxic pollutants from a particular, often industrial site — was the first focus. But in the decades since, stormwater pollution, also known as “non-point source pollution,” has taken the lead when it comes to carrying the most contaminants to U.S. waterways. About 40 percent of U.S. rivers, lakes, and estuaries are not clean enough for fishing or swimming because of pollution from runoff.

And it’s not so surprising, considering the burst in urban development in recent decades. In Washington state alone, the number of people living in the counties that border Puget Sound has more than doubled since 1960. Throughout the United States so much land has been paved that the total amount of impervious surfaces would cover an area about the size of Ohio.

Every time water washes over hard surfaces, it picks up pollutants. Even an area the size of the average homeowner’s roof contributes about 35,000 gallons of runoff each year in the Northwest. And that runoff ends up in the nearest waterway — not the nearest water treatment facility.

“Approximately 50 percent of the region believes that stormwater is treated, is captured and conveyed to a treatment plant of some type. When in fact, this doesn’t take place. Nearly all of this water goes off totally untreated,” says Giles Pettifor, who is part of the municipal stormwater permit team for King County’s Department of Natural Resources and Parks.

How did we get here?

Pettifor explains that we have to remember that governments didn’t begin managing stormwater until 1990, after amendments were made in 1987 to the Clean Water Act.

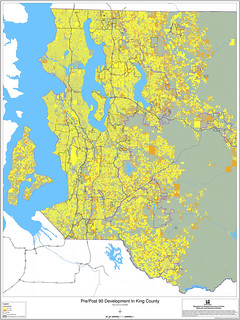

“If you look at regional development, about two thirds of the region was developed prior to that time period,” Pettifor says. “So the vast majority of the land surface around here has no controls on it.”

Prior to 1990, the goal in designing the built environment was to protect the places we live and work from flooding, and that meant directing water as quickly as possible into creeks, rivers and ultimately larger bodies of water.

“If we really want to control the volume of water and pollutants, we’re going to have to go into these areas where there are no controls and install or build new controls,” Pettifor says.

And that would cost millions upon millions of dollars.

King County recently conducted a study of an urban basin called Juanita Creek, where 70 percent of the area is severely lacking in stormwater controls. They used computer models to project what it would take to fully retrofit a basin with enough stormwater management controls to raise water quality levels to conditions that would be beneficial to aquatic life in the areas streams.

They found that it would cost approximately $200 million dollars per square mile to fully retrofit one of these basins.

“Development has taken place over the last 100 years, which got us into the situation that we’re in with stormwater,” Pettifor says. “And it may take us that same length of time to undo, in a sense, a problem that we’ve built.”

Fixing a problem that’s a century in the making

Around the Northwest and across the country, stronger rules are being written requiring cities and counties to adopt new methods for managing runoff. The results are called green stormwater infrastructure or low-impact development.

The idea is to imitate the drainage and filtration that happens in nature. By building structures like rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs, and permeable pavement, more natural forms of filtration and absorption would be added back into the largely impervious urban landscape.

“When it rains in the forest, the water hits the ground and then very slowly seeps into the soil and the soil acts like a sponge. It slows down the water. It cleans the water. It filters it. That’s the point of these green stormwater infrastructure,” says Jennifer McIntyre, a researcher at Washington State University who is studying the biological effectiveness of green stormwater infrastructure.

This move toward green stormwater infrastructure represents a dramatic shift in urban development. And it’s causing concern among local government officials.

“What this means is that in the future we’re going to have a large number of these smaller systems peppered across the landscape, but they’re still going to have to be inspected. They’re still going to have to be maintained,” Pettifor says.

Many urbanized areas in the Northwest, including King County, have begun to test the real-world effectiveness of green stormwater infrastructure.

In Portland, a large-scale project called theTabor to the River is underway to install more than 500 “green streets” within an area that covers 2.3 miles from the Mount Tabor neighborhood to the Willamette River.

Josh Robben of Portland’s Stormwater Retrofit Program weeds a rain garden that is part

of the Tabor to the River Project, a pilot program for green stormwater infrastructure.

Credit: Amelia Templeton

This neighborhood, like many in the Northwest, was developed at the turn of the last century, when it was common practice to direct stormwater into the sewer system. But the pipes in this combined system were not built to accommodate modern-day needs.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the neighborhood began to have chronic problems with sewers backing up and combined-sewer-stormwater overflows releasing raw sewage directly into the Willamette River. The problem needed to be fixed. And the cost for this one neighborhood was expected to reach $144 million to build bigger pipes.

But officials within the City of Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services saw an opportunity to build a series of strategically located rain gardens, green roofs, bioswales and permeable pavement. They have built them in the right-of-way and on private property. If these methods can divert stormwater, it will relieve pressure on the city’s overwhelmed sewer system and reduce the need to enlarge the pipes.

And in following this plan, the budget for the project has dropped to $81 million — a savings of $63 million.

The Big Green Stormwater Experiment

Because green stormwater methods are relatively new, little is known about how long structures like rain gardens last or what ongoing maintenance permeable pavement will need — or even whether these methods make any difference when it comes to protecting the environment.

“People are running out and building rain gardens and that’s great, but there is the potential for them not to work because we don’t know very much about them yet,” McIntyre says, as she looks out at the rain gardens and bioswales being tested within Washington State University’s Low Impact Development Research Program in Puyallup. It’s part of the Washington Stormwater Center, a new, one-of-a-kind facility for testing sustainable stormwater management.

Researchers here are trying to find out what soil mixtures and plants are best to use in rain gardens, how often plants will need to be replaced, and how long these systems hold up to under a continuous input of contaminants coming from polluted runoff.

“We know that (rain gardens) can reduce some of the contaminants in stormwater. We know that it can reduce the flow of stormwater. These are all really good things,” McIntyre says. “But is that enough? Is it enough to protect wild fish and their food web from some of the harmful effects of stormwater runoff?”

That’s what McIntyre’s latest research project it trying to figure out — specifically how runoff impacts juvenile coho salmon. She’s leading a team that’s conducting research as part of a joint collaboration between Washington State University, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and NOAA’s coastal storms program.

The experiment began on a rainy morning that broke a string of 50 days without precipitation. McIntyre’s team collected 400 liters of murky liquid that came off of a Seattle highway smelling, “like a highway with a slight tinge of cigarette butts.”

They loaded the glass carboys into a pickup and trucked the collected runoff down to the facility in Puyallup.

Next they filtered half of the polluted water through soil, mimicking what happens in a rain garden. Then they filled a series of aquariums — half with the straight highway runoff, and half with the runoff that had gone through the rain garden filtration.

The two darker colored carboys contain straight highway runoff. The two lighter

colored carboys contain runoff that has been filtered through soil columns.

Credit: Katie Campbell

The researchers then put 10 finger-length coho salmon into each aquarium and waited to see what would happen.

McIntyre’s plan was to monitor the salmon for four days and then dissect them and take samples of their hearts, gills, bile and liver. The goal of the study is to gain a better understanding of the sublethal effects of that the toxins in stormwater have on fish.

But within 12 hours, McIntyre returned to the aquariums and discovered the fish in the aquariums filled with straight highway runoff were all dead.

She then checked on the fish in aquariums filled with runoff that had been filtered. And to her surprise, they were all still alive.

Even four days later. They were all swimming around in the rain-garden-filtered runoff. “They all seemed fine,” McIntyre says.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that they were healthy. McIntyre continued the dissection and gathered samples from all the fish in the study into order to suss out any sublethal effects. She won’t know more until lab results come back and she has a chance to analyze them.

One thing, however, is very clear.

“I think it’s really telling that we can take something as concentrated and toxic as highway runoff after a long dry spell and pass it through soil columns and have it no longer be acutely lethal to fish,” McIntyre says.

Meanwhile Beneath The Surface of Puget Sound

While McIntyre searches for answers in the lab, Laura James continues to raise awareness out in the world. And she’s doing so by documenting the effects of stormwater with her camera.

“I thought, ‘If I can capture this on film, if I can share this, it will truly give our waters a voice,’” James says. “Because people see it and they just stop what they’re doing and they look. They make a connection. They’re shocked.”

Earlier this week, James saw a chance to shock us once more. She set up a time-lapse camera at the mouth of a stormwater outfall in West Seattle, an outfall that she has taken to calling, The Monster.

Then she waited for the first big rains of the season to wash another slurry of polluted runoff into the Sound.

Here’s the time-lapse video that starts just before the rains came Sunday afternoon (outflow begins at about 0:50):

“I see Puget Sound and our oceans as a reflection of us. They’re a reflection our humanity,” James says. “And the storm drains are a conduit of our humanity running in there.”

In addition to documenting the stormwater outfalls of Puget Sound, James is leading an educational campaign called Don’t Feed The Tox-ick Monster to inspire area residents to take simple actions to help curb stormwater pollution.

“It’s everybody’s problem. And it’s everybody’s solution,” James says. “We can’t expect the government or the nonprofits to fix it for us, we have to fix it.”

Writing, video and photography by Katie Campbell unless otherwise credited. Audio by Ashley Ahearn. InvestigateWest’s Robert McClure contributed to this report.

A growing number of cities and neighborhoods around Puget Sound are doing their part in responsible and sustainable stormwater management. The City of Kirkland and Finn Hill’s NE 138th Street installed a retrofit cluster of eight rain gardens just this past weekend. They protect the upper Juanita Creek basin, mentioned in this story as needing stormwater controls, and it flows into Lake Washington. Kudos to them for stepping up and addressing the older, already built environment. They are worth a drive by – a map and photos are at the link below.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10151259729635465&set=a.10151256430485465.504925.582940464&type=1&theater

Thanks for tackling this topic. It is such an important and little understood issue. My community of Hood River is right on the Columbia River. It’s sad and frustrating to see thousands of cigarette butts (in addition to all the other things mentioned in the article) that people put in the street. Not understanding that the filter is not organic and will go directly into the river. Sigh. Thanks again. Hope you spread this article far and wide.