A thrift store. Thousands of costumes. An attorney general’s lawsuit.

“Every used item in this store was PURCHASED from our non-profit partners.”

Emblazoned on the wall behind cash registers at a Value Village thrift store in Bellingham, Wash., the meaning of the feel-good message in bold lettering couldn’t be missed by shoppers at the store’s grand opening in 2011: The purchase of slightly used pants, a vintage jacket and other thrift-store treasures is an act of charity.

The black T-shirts worn by cashiers carried a matching message for bargain hunters with a heart of gold: “Good deeds. Great deals.”

Ubiquitous promotion of charitable activity is a big reason why Value Village’s corporate parent, Savers, Inc., does more than $1.2 billion in business annually. For years it has been the single largest player in the prosperous and growing industry of for-profit thrift stores.

Thrift has proved lucrative for the firms’ executives. Board Chairman Tom Ellison, for example, owns a waterfront mansion in the same exclusive Seattle suburb where Bill Gates lives.

But Savers’ claims about doing good for charities appear to be vastly overblown. Behind many a great deal at Value Village is a pretty meager good deed. Behind others there appears to be none, InvestigateWest found.[1]

Sometimes Savers’ charity partners have received less than 5 percent of sales revenue on goods donated on their behalf, InvestigateWest found. Overall, it appears that between 8 percent and 17 percent of the firm’s revenue ends up with charities.

Sometimes Savers’ charity partners have received less than 5 percent of sales revenue on goods donated on their behalf, InvestigateWest found. Overall, it appears that between 8 percent and 17 percent of the firm’s revenue ends up with charities.

Meanwhile, Savers does not routinely tell donors how much of their used-goods donation actually goes to charity. That may mislead donors to overestimate their good deed, and according to tax experts and charity-watchers, take a tax deduction that is far too high.

Savers refused to be interviewed or provide answers in response to written questions for this story.

Today Savers is aggressively expanding. From 2009 to 2014, Savers grew at a rate of about 5 percent each year and opened or acquired up to 20 stores a year, according to industry-research firm IBISWorld. The company now reports running more than 330 stores in 30 states, Canada and Australia, and employing 22,000 workers. The chain increasingly competes with longstanding nonprofit thrift stores that devote most of their revenue to those in need.

And Savers, after decades of relying heavily on its partner charities to gather goods for sale at its stores, has embraced a new strategy: asking donors to drop off merchandise directly instead of donating to charities that then bring the goods to Savers. Savers “purchases” this merchandise by donating money to charities in the donors’ name, but at a price far less per pound than merchandise brought in by the charities themselves.

The collection strategy, employed by Savers at least since 2005, was highlighted in a 2012 Standard & Poor’s corporate rating of Savers projecting that Savers’ gross profit margin would increase, “reflecting an increase in higher margin on-site donations.”

And it has paid off. From 2005 to 2010 Savers was the nation’s fifth-fastest-growing discount retailer, according to the trade journal Chain Store Guide. And since 2006 its revenue has more than doubled, according to Moody’s Investor’s Service, to $1.2 billion, although privately owned Savers does not disclose its financial performance to the public.

Meanwhile, at least six of the more than 100 charities associated with Savers stores have severed ties with the company over the last six years, at least two citing terms that were too unfavorable to the charities.

One charity that pulled the plug was the Boston-area Big Brother Big Sister Foundation, which now is netting three to four times the revenue it received under the Savers deal by operating its own thrift store, according to Steven Beck, director of the Boston nonprofit.

“If a charity is making 4 to 6 percent, that’s pretty unbalanced,” Beck said. “If you’re making a million, and we’re making $40,000, how is that helping charities?”

“It may be legal, but it’s not right.”

There’s no question that charities make money they wouldn’t otherwise have.

“I can’t say enough good about our relationship with Savers,” said Lori Konya, CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Northern New Jersey and its donation-gathering subsidiary Clothes For Kids’ Sake. “Federal funding has dried up. A lot of government funding has dried up for nonprofits and I’m not even sure we’d be in business without Savers.”

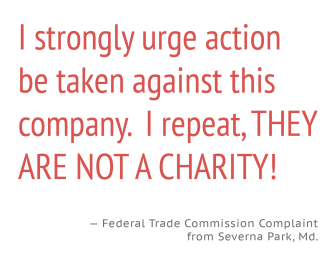

But critics say Savers’ consumers and donors are being deceived because so little of the stores’ revenue actually reaches the charities.

But critics say Savers’ consumers and donors are being deceived because so little of the stores’ revenue actually reaches the charities.

Consumer advocate Sylvia Kronstadt, formerly a fraud investigator at New York City’s Department of Consumer Affairs, argues that consumers and donors should shun Savers because of its business model.

The company, she told InvestigateWest in an email, “preys on donors’ good intentions to create fabulous wealth for itself.” To her, “the charities who ‘partner’ with Savers are guilty as well, for allowing their names to be used in exchange for a few pennies on the dollar.”

Decades before Macklemore’s monster 2012 hit “Thrift Shop” spotlighted an evolution in Americans’ shopping habits, Savers perfected a “community service” marketing veneer that suggests its main goal is to help charities.

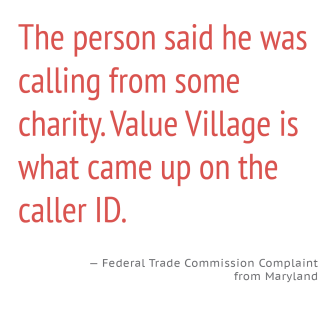

“A lot of people coming in here think we are a charity,” Sean Macrae, a floor worker at one of Savers’ Value Village stores in Seattle, told InvestigateWest in June 2014, even though Savers is registered as a for-profit business in Washington state and elsewhere.

And why wouldn’t consumers walking into one of Savers’ roomy, brightly lit stores think that when they see the prominent logo of a local nonprofit?

Founded by the son of a Salvation Army executive in San Francisco’s Mission District in 1954, Savers created a business model that today is growing increasingly widespread: the for-profit thrift store.

Goods sold in Savers’ stores come from charities’ collection bins, at-home pickups scheduled by telemarketers paid by Savers or a nonprofit partner, and special fundraising drives. Plus, of course, the in-store drop-offs Savers now favors. Potential donors are targeted with radio and TV ads, direct mail appeals, postcards and brochures.

Charity-watchers say Savers and stores like it are quietly reaping a bonanza on donated goods, giving back minimally to charities while spouting slogans like “Donating to Value Village is a great way to Donate to Charity.”

Savers’ for-profit status “needs to be disclosed at the point of donation,” said Daniel Borochoff, president of the American Institute of Philanthropy and charitywatch.org.

Savers’ nonprofit competitors are pointed in their criticism.

“It would not be deceptive if Savers stated clearly on its doors that they were collecting on behalf of certain charities and let you know whatever percentage that amounted to,” said Michael Meyer, a vice president of Goodwill Industries International. “Now … the presentation is creating enough grayness that it’s not clear to the consumer.”

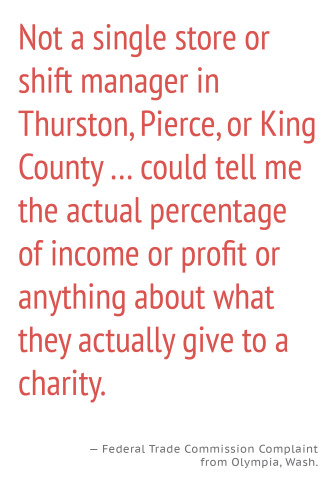

Although most states do not require for-profit thrift stores to disclose how much they pay charities, InvestigateWest obtained contracts between Savers and charities filed with state officials in Washington and documents from Minnesota describing prices Savers paid charities there. InvestigateWest also analyzed information gathered by California for Savers stores doing business with two Silicon Valley charities. Taken together, they show that Savers’ partners are receiving only a small fraction of the sale price of the donated merchandise. Interviews with more than a dozen former and current employees corroborate these records.

The smallest percentages of revenue paid to charities over the last 15 years by Savers, according to the California records Savers filed,[2] came in 2001 when Big Brothers, Big Sisters of East Bay, in Oakland, received .02 percent of the revenue raised from donations on its behalf. The same year Hope Rehabilitation Services in Santa Clara received just .87 percent of Savers’ revenue, California public records state.

The most recent California records, from 2013, state that Savers is sending between 4 percent and 17 percent of revenue to charities.[3]

Overall, Savers says it paid $200 million to charities in 2014. If the $1.2 billion in annual revenue that Moody’s estimates Savers made for the year ending in April 2015 is accurate, that works out to Savers keeping roughly 83 cents of every dollar it takes in. Charities get 17 percent. [4]

Savers’ largest nonprofit competitors, which are required by federal law to report their finances to the public, spend a large majority of revenue on helping people in need. For example, even though Goodwill Industries International has been criticized for extravagant executive salaries, its 2014 audited financial statement reports that it devoted 95 percent of its revenue to programs that help the disabled and others who have difficulty securing work.

Although Savers would not respond to InvestigateWest’s questions, public records show how the firm has defended itself to government officials.

In a letter InvestigateWest obtained through the Washington Open Public Records Act, the Washington State Charities Division asked Value Village in 2002 about whether it solicits, and is therefore required to register as a commercial fundraiser. Savers general counsel Bradley Whiting responded in part:

“We do not solicit for donations or contributions on behalf of any organization, nor do we donate ourselves to any organization. All merchandise obtained from the local not-for-profit entities is purchased from the entities at a commercially negotiated price, and is not tied to any subsequent sale to the public. Our relationship with the entities is strictly one of purchaser and supplier.”

Yet the price discrepancies between what Savers pays the charities and how much items earn on the sales floor are stark: A tie that Value Village might pay a nickel to buy from a charity sells for $4.99. A vintage women’s top that costs Value Village a dime sells for $9.99. A purse that Value Village gets for about a quarter retails for $12.99. A vase, which Value Village doesn’t pay anything for under the contracts InvestigateWest reviewed, goes on the sales floor for $14.99. Those figures, based on one typical contract and purchases made by InvestigateWest at a Seattle Value Village, vary from store to store and nonprofit to nonprofit, but across its operations, Savers’ business model is based on paying a few dimes per pound for clothing it sells at secondhand-retail prices — a considerable margin.

Charity watchers’ criticisms are muted by Savers’ practiced and ever-evolving marketing campaign, which has built a strong and loyal customer base with slogans like “Your donation of clothing and household goods just became funding for a local nonprofit.”

Calling itself “the thrift superstore with a community conscience,” Savers defends itself against supporters of nonprofit thrift store operators, stating that it offers medium-sized nonprofits a way to earn money even if they can’t open their own thrift stores, like behemoths of the industry, Goodwill and The Salvation Army. Indeed, some of Savers’ charity partners have done business with the chain for decades.

Savers spokeswoman Sara Gaugl told Washington State officials in a 2013 letter responding to a consumer’s complaint that the company pays nonprofits for all the items delivered, even though nearly three-quarters are not suitable for resale. The rest are “responsibly recycled,” she wrote. Much of that involves selling merchandise in developing countries.

Gaugl’s letter came in response to a complaint filed with the Washington State Attorney General’s Office by a consumer upset at what she considered false and deceptive “fundraising representations.”

The consumer’s complaint cited numerous in-store fundraising appeals and asked why the company had not registered as a commercial fundraiser. “Inside the store, there are more signs, in addition to canned announcements every few minutes plus bookmarks scattered everywhere,” the consumer wrote. She also urged the state’s attorney general to undertake an investigation of Savers.

However, the state Attorney General’s Office, responded by passing the complaint on to Savers and closing the matter in March 2013.

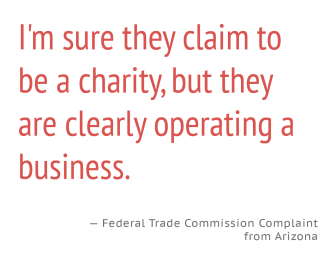

Minnesota’s Attorney General took a different approach, prompted by “many complaints from consumers,” according to spokesman Ben Wogsland.

Following a year-long investigation, Minnesota Attorney General Lori Swanson sued Savers in May 2015, accusing the company of deceit by “convincing people to shop at Savers stores under the guise that Savers is or has the aura of a nonprofit or benevolent organization, such that their purchases will benefit a charity.”

“This masks Savers’ actual status as a for-profit entity that receives the lion’s share of the value of donations people make to benefit charitable organizations,” said the suit, which sought among other things to compel the company to be more forthcoming with consumers and donors. Also: “Examples abound of Savers’ attempts to blur its mission and identity with that of charities.”

The lawsuit was settled in June, with Savers — without admitting fault — agreeing to pay $1.8 million to charities and provide more transparency to donors and shoppers.

“Savers is holding themselves out as a ‘do good’ organization. But they should not be soliciting for goods that charities aren’t benefitting from,” Wogsland said.

He added: “We have no reason to believe that they’re operating any differently in other states.”

Swanson in May notified other states’ attorneys general of her findings.

So far none has taken action.

Jody Orbits, president of Eastside Community Aid thrift store.

Some who have worked at Value Village understand the criticisms.

“You see some big poster with a big Guatemalan baby face on it, and think that’s what it is about,” said Catherine Brophy, who worked her way up from cashier to assistant manager at a Value Village outside Seattle. In reality, says Brophy, who now works for Habitat for Humanity’s ReStore, “The main focus of Value Village is about making a profit. It’s all about ‘what are the numbers?’”

Just across the parking lot from the 24,000-square-foot Value Village where Brophy worked sits a tiny thrift shop called Eastside Community Aid. Virtually all the earnings produced by the 60 volunteers who take shifts at the nonprofit secondhand store support its mission and programs, including causes such as low-income housing, food banks and fighting domestic violence. The small store competes for donors and shoppers with the big-box, commercial competitor next door and its huge, directional signage, crafty marketing and a voluminous share of parking spots.

“People think they’re giving to the community, but it’s unclear how much,” says Jody Orbits, manager at Eastside Community Aid. “They just don’t know the full story of where those donations are going.”

“Well, this is America,” Orbits continues. “They’ve got a business. It gives people jobs. But it would be nice if they gave a little more back to charity.”

Savers is a business, but is it abusing charities and hoodwinking donors? One major accusation leveled by the Minnesota attorney general is that Savers pays its partners nothing for household appliances, recreational equipment, bric-a-brac and other so-called “hard goods.”

An InvestigateWest review of eight contracts between Savers and charities in Washington State found that Savers appears to pay nothing for certain donated items. The charities’ donations are required by the contracts to be weighed and paid for but the housewares and so forth are “included in the cloth price.” Translation: Charities are required by contract to bring in the hard goods. They just don’t get paid extra for them. Several former Savers employees and an executive at a former Savers charity partner confirmed this information to InvestigateWest.

“My understanding was that we got paid per pound for the clothing; ‘miscel’ we didn’t get paid for,” said Brian Holloway, director of advocacy and family support at the Arc of Spokane, Wash., charity, because its value is supposed to be covered by the price paid for clothing. Arc of Spokane severed its relationship with Savers in 2013 to open its own thrift store.

Yet Savers’ marketing frequently blurs the distinction:

On the “Donate” page of the Savers website: “Every donation of gently used clothing and items you make supports a nonprofit in your community.”

On brochures distributed at retail stores: “We partner with local nonprofits and pay them for all the goods donated at our stores.”

On a promotional bookmark: “Value Village pays local nonprofits every time you donate.”

Elsewhere on the Savers website until recently: “Besides getting great deals, another great thing about shopping Savers stores is knowing that with every purchase or donation, you’re helping to make a difference in peoples’ lives.”

And sometimes the same message can be found on charities’ websites too, like this passage from Clothes For Kids’ Sake:

“We collect donations of gently-used clothing, housewares, books, toys, etc. from members of our local community and deliver these items to our neighborhood Savers store. The revenue from the items sold go directly to your local Big Brothers Big Sisters agencies.”

Savers’ practices are well-known among charity watchers and those in the resale business themselves.

“Savers and other for-profit stores should be clearly articulating the amount that is actually going to the charity and clearly telling donors where the rest is going,” said Kris Kewitsch, director of the Minnesota-based Charities Review Council.

“It’s not clear to the public who’s benefiting,” said Adele Meyer, president of the main trade group for thrift stores, NARTS the national Association of Resale Professionals. “They’re privately held but they don’t post it; everything above operating costs goes into the hands of a private company.”

“The true issue lies at the core of the industry: who benefits from me donating my stuff to a charity?” said Beck of the Boston-area Big Brother Big Sister Foundation. “Why should I give if the charity only gets a small share of the money?”

Charity watchers say donors and shoppers shouldn’t be left to guess how much money makes its way from the sales floor to Savers’ charity partners. But the company has resisted a legal requirement to do that in its home state of Washington.

At least six times since 1987 authorities in Savers’ home state of Washington told the company to register as a commercial fundraiser under a state law meant to protect the public from deceptive fundraising. Commercial fundraisers must report how much they raise for charity and what percentage they keep for themselves.

Finally, in early November 2014, Savers, under pressure from a Washington state assistant attorney general, at last conceded. It is now registered as a commercial fundraiser in Washington, and is required to report how much it is giving to charities. But the company has not yet revealed what proportion of its revenues go to charity.

Finally, in early November 2014, Savers, under pressure from a Washington state assistant attorney general, at last conceded. It is now registered as a commercial fundraiser in Washington, and is required to report how much it is giving to charities. But the company has not yet revealed what proportion of its revenues go to charity.

That’s the result sought for decades by officials in the Washington Secretary of State’s Office Charities Program, including Rebecca Sherrell and Tabatha Blacksmith.

Although Savers did not respond to InvestigateWest’s questions, it did answer a five-sentence statement that says in part, ” In some states where we operate, our partnerships with nonprofit organizations may be considered fundraising. Therefore, we are ensuring we comply with all applicable charitable fundraising requirements, and as appropriate, we have and are registering as a professional fundraiser.” A Savers web page lists 14 states where the company has registered.

In Minnesota, it took the attorney general’s lawsuit to get Savers to promise to disclose the percentage of a donation’s value that actually reaches the charity, including differences for in-store donations. Under the settlement, Savers will also file annual reports with the state outlining the value of donations, expenses and payments to charities; certify that donations solicited on behalf of a particular charity actually benefit that charity; and for the first time, be prohibited from not paying for non-clothing goods collected by charities.

For Savers’ donors elsewhere, however, an equal dose of transparency may still be hard to come by. Critics charge that how Savers’ collects donations encourages donors to overestimate the value of their charitable contribution.

InvestigateWest documented several instances in which Savers stores gave donors the impression the entire value of the goods is deductible.

“Please insert what you feel is fair market value of the merchandise,” said a receipt for Savers’ donors in Kansas City. A Seattle-area store distributes receipts with similar wording.

In a report that predated filing suit against Savers, the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office criticized Savers for misleading donors, resulting in their “claiming tax deductions for donated goods for which the charities receive no payment.”

Sherrell, of the Washington Charities Program, advises consumers who get a phone call asking for donations for charity to ask what percentage actually goes to the charity.

“I hope this Minnesota lawsuit opens the eyes of the donating public,” she said.

Robert McClure contributed to this report.

InvestigateWest thanks the Fund for Investigative Journalism for its generous support of this reporting project.

[1] Beginning in spring 2013, InvestigateWest procured and reviewed government records, private financial analysis, charity tax documents and financial filings, and conducted extensive interviewing with current and former employees, government officials, tax experts, thrift-store industry officials and others.

[2] Savers appears to have failed to file a number of required reports over the last 15 years. At least five years’ worth of financial reports were missing covering the years 2007 to 2011, according to a letter from the California Department of Justice to Savers on Feb. 12, 2012.

[3] Savers has failed to file legally required reports, the California Department of Justice said in letters to the company in August, after InvestigateWest inquired with the Justice Department as to their whereabouts, and again earlier this month. Filings for the Epilepsy Foundation of America Northern California and the Epilepsy Foundation of Los Angeles are missing for the last five years, the Justice Department’s Oct. 13 letter to a Savers’ subsidiary said. Further, Savers has told California officials that the revenues-earned figures it has supplied to document its relationship with other charities include an unspecified amount of revenue from merchandise Savers purchased “from for-profit resellers, as well as vendors of new merchandise.” So the percentage going to charity would be more than what the California records state — but how much more is not documented publicly.

[4] Hoovers estimates Savers’ annual revenues at $2.4 billion. That would mean about 8 percent of Savers’ revenue is going to charity.

I’ll start with my qualifications where this issue is concerned. I am privy to the operation of 1 charity partner that provides product to a for-profit thrift store. This relationship has existed for 25 plus years without the charity once expressing a desire to open its own retail locations. The relationship of purchaser and supplier has proved beneficial for a quarter century. The public dilemma is one of semantics. Thrift store connotes a charity connection. Established charities such as Salvation Army and United Way are discovering that running both sides of the thrift store equation is not feasible. The relationship between purchaser and supplier drives efficiency through competition. The for-profit takeover of thrift stores is a result of differing philosophies. Retail requires a drive for profit to survive. The charitable collection of clothing and household items takes a dedication to customer service. These 2 philosophies are not always complimentary.

The bottom line is the for-profit thrift stores would not have to be charity affiliated at all if they could provide their own product. The charities that provide that product are collecting enough money not only to cover their operating expenses but to also apply the margin of profit to their stated purposes.

The true problem in this relationship is the amount of information people are either not aware of or are willing to forget to promote their own agenda.

I have known about this for over 20 years the. Owner has had waterfront property on lake Washington for over 20. Years. I stopped giving to the blind because they sell bags of stuff to VVillage for pennies on the pound. I am surprised this is just coming out! I think people just ignored this fact!

I greatly appreciate the work done for this article, and wish it would be picked up by more news outlets in Washington. I naively assumed–like many people–that all items donated to Value Village were sold with proceeds over operating costs going to charity. If smaller charities can function by selling donated items to Savers at a tiny percentage of their retail price I suppose that’s of some benefit, but I don’t care to help further enrich Savers’ executives. In future I will donate directly to Goodwill or the Salvation Army.

As a former employee of Savers in California I’ve seen what they say they do with their donations they really don’t. I would have to accept the donations and sort them and the items like clothing and furniture I would say is acceptable and ready to be priced and sold the manager would turn around and tell me to destroy and trash. I would price stuff and put them out on the floor and would end up getting yelled at by manager for underpricing them and wanting me to re-price them at or above face value. And the work conditions they expected of me was completely cramped, at times dangerous and completely rediculous. I ended up finding a new job and quiting ASAP. I haven’t recommend them to anyone since

I believe that the intent of this article is purely to discredit Savers and does not seem like a purely unbiased opinion. The claim in this report that “Goodwill Industries International has been criticized for extravagant executive salaries, its 2014 audited financial statement reports that it devoted 95 percent of its revenue to programs that help the disabled and others who have difficulty securing work.” this CLAIM from yet an Audited Financial statement, must be investigated MUCH MUCH further. Locally, this organisation is Government subsidized using $3,706,608 of tax payers dollars with a revenue exceeding $21.8 million and expenses reported to be at $20 million including executive salaries. Our local NON-PROFIT organisation is purely made of volunteers with ZERO salary to the Board of Directors. Savers does not make claim to be a non-profit organisation they purely purchase from non-profit organisations which in turn allows organisations such as ourselves to even exist. Where Goodwill states they are a charitable organisation as per your comments above. There is definitely a distinct tone of propaganda here, especially in the states of Minnesota and Washington.

Got one of those in my “city” Pembroke Ontario Canada…No difference here…they check out “select”donations to see if they are collectables & then leverage the price accordingly….Here they have a “pet” charity that gets the proceeds